While you may have heard of the Seven Principles of Leave No Trace, it’s common for people to be unclear on the specifics. Not to mention, most guidebooks tend to recount the basics without really going into specific actions that you can take to ensure you’re caring for the environment while you’re out adventuring. We’ve put together a comprehensive look at the principles, as well as eight lesser-known tips specific to hikers.

In a hurry?

If you just want to skip to the lesser-known tips, use the links below:

- # 1 When Walking Off-Trail Use the ‘Fan Out’ Technique

- # 2 When Walking On-Trail, Go THROUGH Not Around

- # 3 When Making Camp, Don’t Alter a Site for Your Campsite

- # 4 Consider the ‘Campsite Highways’ You’ll Be Creating by Regularly Moving Around Camp

- # 5 Do You Really Need a Crackling Campfire?

- # 6 Approach Rubbish Disposal With Benevolence by Carrying Out All Rubbish, Not Just Your Own

- # 7 Look After Your Personal Hygiene and the Environment by Using Low-Impact Methods

- # 8 Share Your Travels Online Responsibly and Respectfully

First Thing’s First—What’s ‘Leave No Trace’ and what are the principles?

The ‘Leave No Trace’ (LNT) principles—are a set of guidelines that are intended to inform, educate and direct adventurers in how to respect and care for the environment when we’re out there exploring.

Leave No Trace is for both on and off-trail trips, so applies to every single hike you’ve ever done and will do in the future.

Now, as with any set of guidelines, especially ones that are designed for such a wide audience, there are varying interpretations and uptakes. LNT purists might wag their fingers at some behaviours they see out on the trail, while others might look at them incredulously, considering them to be overcautious or ‘OTT’.

And what’s more, new research is continually evolving, meaning that the guidelines are always adapting.

So the important thing here is to try your best—educate yourself, speak to seasoned hikers for tips and always plan your trips with the environment in mind.

At this point in time, there are seven principles to follow. Before we jump into the ‘lesser-known’ aspects of the principles, let’s go over what the ‘official’ principles are:

1. Prior planning prevents poor performance

You may have heard this statement in a corporate setting and cringed, but it’s an important aspect of getting out into the wild.

Planning prevents accidents and ensures you will have the skills to deal with an incident if something does happen.

Preparation can look like completing a first aid course before heading out, planning your route to include water fill-up opportunities, planning what food you bring to minimise waste or carefully choosing the protective clothing you’ll pack.

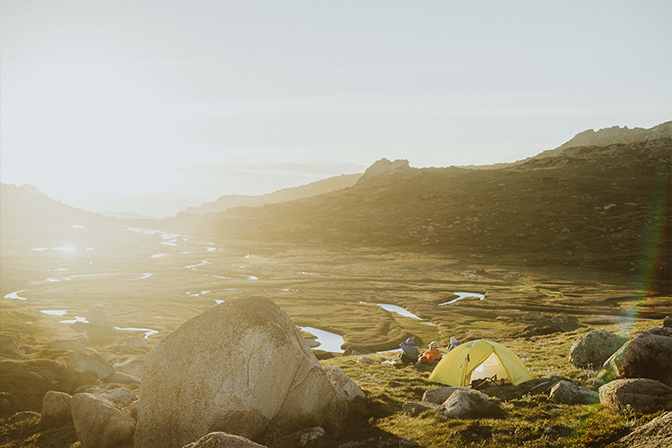

Camping at Kosciuszko National Park. Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

2. Travel and camp on durable, hardy surfaces that will spring back more easily

When you set off for a hike, it’s not often that you’re conscious of every single step. But it is important to be conscious that some surfaces you’re treading on will take longer than others to recover.

This can be a tricky one as most of us aren’t expert ecologists.

So at a minimum, try to learn as much as you can about the types of vegetation you’ll be walking on before you head out. A quick Google might uncover information about endangered lichens or grasses, which you can then avoid when hiking.

Particularly sensitive areas include river banks (riparian zones), wet grasslands and fragile flower fields (to name a few).

3. Dispose of waste thoughtfully and responsibly

It sounds pretty simple doesn’t it? Pack out your lunch plastics and she’ll be right, right? Wrong.

It’s much more than that.

Disposing of your waste refers not only to your food packaging, but also to your organic food scraps, your human waste, sanitary items, toilet paper (in some circumstances), broken gear or pieces of gear that have broken off, and much more.

Make sure you’re not missing what some call ‘micro-rubbish’—those tiny pieces of foil that unknowingly made their way to the ground, beer bottle caps and strapping tape or bandaid pieces.

One of the most common pieces of micro-rubbish I see is those little circles of foil from the back of a pill blister packs. So annoying!

When you’re planning your trip, think about what meals and meal containers you can bring that will prevent you from discarding waste while you’re out there, consciously and unconsciously.

Burning your trash isn’t a great option, so don’t rely on that. Often small food and packaging particles aren’t burnt and so they end up left in the firepit.

It also applies to how you treat waterways—instead of washing your dishes in the creek, you want to grab some water using a clean pot and carry it about 50m away to wash up. This applies to washing your bodies too, as you’ll most likely have harmful chemicals on your skin from sunscreens and other lotions.

And finally, poo. Human waste needs to be disposed of responsibly too!

Pack biodegradable toilet paper, and only bury if the soil is rich enough and loose enough to dig a deep hole, ideally dug with lightweight trowel. If not, carry the poo out just like all the other rubbish.

If you menstruate, think about using a menstrual cup. If you can’t or don’t want to, make sure you carry out all tampons and pads with you.

4. Leave what you find—take a photo instead!

The basic premise behind this principle is to leave the beautiful things you come across while hiking as they are and where they are, for the benefit of other hikers.

By not taking that gorgeous rock home, you’re giving others the opportunity to experience the beauty just as you did.

But it’s not just about not taking items away with you, it’s also about leaving things as you find them both for the benefit of future hikers, and the flora and fauna that might be relying on them for their food, water or shelter.

So you shouldn’t be cutting or altering trees or vegetation, building shelters unless it’s an emergency, picking flowers, or touching or removing anything with cultural or historical significance.

Enjoying the view. Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

Cooking responsibly. Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

5. Manage fire risk through responsible campfire and stove management

Here in Australia, bushfires have recently caused unimaginable damage.

While drought and poor land management practices did contribute to their severity and widespread damage, we also know that poor individual fire management by recreational users of naturespaces was responsible for at least a portion of the fires of the summer of 2019-2020.

But it’s not just the bushfire risk we need to worry about, it’s also the potential negative ecological impacts. Creating new fire sites, moving branches for wood and effectively putting out the fire are just some of the considerations when managing campfires.

6. Respect wildlife from afar

For the average hiker, there’s absolutely no reason why you should need to ‘get a closer look’ at the wildlife that you come across.

Not only can it scare or agitate them, it might be extremely dangerous to approach wildlife.

And, given that you’re in the wilderness, you might be quite far from help if you get scratched or bitten.

It might seem heartless or counterintuitive, but it’s important that you don’t pick up sick or injured animals either, especially young ones. Some animals will abandon their young if they’ve been picked up by humans, and that’s the last thing you want.

Making sure that you pack away all your food and food scraps is extremely important too, by using airtight containers, dry bags and double-bagged garbage bags.

It’s also worth mentioning that most Australian animals are nocturnal or crepuscular (only active at twilight and in the dark), so they will likely need to visit the local water source at night time.

I know this is a hard one, but try to think about what routes they might be taking. If it’s possible for you to camp somewhere that doesn’t impede that important nightly migration, it’s a good thing to do.

7. Be considerate of other human visitors

This is one of those things that you’d assume is common sense… but it isn’t.

Trying not to be too loud, respecting other people’s space and keeping pets closely controlled or on a leash, are just some of the ways that you can respect your fellow hikers.

Technology is a great thing, make no mistake, but it’s important to keep in mind that many people are escaping when they head ‘out bush’. Pumping loud music on bluetooth speakers or flying a drone around people’s heads is what I’d call ‘a dick move.’

It’s also important to observe other types of trail etiquette, such as letting those heading uphill pass on narrow paths, and for cyclists, it’s good etiquette to give way to foot and equestrian traffic.

Now that we understand what the seven official Leave No Trail principles are, here are some lesser known aspects to the principles that are worth considering next time you head out on the trail.

# 1 When Walking Off-Trail Use the ‘Fan Out’ Technique

The majority of most people’s hiking will take place on marked trails. These are often specifically designed by National Parks authorities and professional teams, but not always.

Following marked trails is the right thing to do—there are specific reasons why that route was chosen, and the very existence of the trail in the first place indicates that this route receives higher traffic levels than it could naturally withstand.

However, when you’re walking off-trail where no foot-padded trails exist, and you’re walking in a group of people, it’s best to spread out or ‘fan out’.

By taking separate trails rather than following the person in front of you, you’ll give the ground a chance to spring back after you pass through.

Of course, there are fragile terrains that need to be completely avoided, but in open grassland, for example, fanning out is best-practice.

Now the lines of etiquette do blur a little here, so you’ll need to employ some personal judgement, but it’s worth mentioning that if you notice a very slightly padded trail, it’s also best to avoid that.

This could be either a trail that a small group unknowingly padded down, or the impact of an animal’s regular route.

Either way, you don’t need to contribute to, or disturb the faint path.

# 2 When Walking On-Trail, Go THROUGH Not Around

Now I know that it can be tempting to hold up the ‘cleanest-socked-hiker’ at the end of a hike as a samurai-like, surefooted hiking master…

But honestly, if they were hiking along muddy trails and have emerge spick and span, I’m going to assume one of two things; either they’re an Olympic long-jumper or pole-vaulter, OR they walked around the muddy puddles instead of splashing through them.

Walking around creates new paths that others will follow without thinking, and it can also destroy the vegetation around the puddle, including their root systems that keep soil in place. If this happens, guess what… the puddle gets bigger!

So if you come across a puddle, let it welcome you with open arms and just splash right through.

And you know what the real badge of honour will be? You guess it—the muddiest boots.

Hiking in Kosciuszko National Park. Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

Setting up camp. Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

# 3 When Making Camp, Don’t Alter a Site for Your Campsite

Choosing exactly where to pitch your tent shouldn’t be a matter of making sure it feels like you’re sleeping on a bed of clouds (although that is super lovely).

You also need to take into consideration how fragile the vegetation and soil is, what existing campsites are around, any regular animal routes, and other campers around you.

Altering a site is a big no-no. Aside from moving a few very small fallen sticks, as much as possible, you shouldn’t be moving branches or rocks around to make space for your tent.

Ideally, if there’s an obvious tent pad (somewhere where others have camped in the past), you should camp here (as long as it is far enough from the trail, animal routes and other campers’ established sites for the night).

It’s also not ok to cut branches from trees (dead or alive) to clear a site, or a pretty view from your campsite either.

When you leave the next morning, make sure you try to leave the campsite as clean and naturalised as possible. This could mean rubbing out any obvious scuffles, and it definitely includes picking up all rubbish, and dealing with any campfires you may have had.

# 4 Consider the ‘Campsite Highways’ You’ll Be Creating by Regularly Moving Around Camp

This is similar to my point about being careful about unintentionally creating paths when hiking off-trail, but applies on a micro level to your campsite setup.

Let’s imagine you’re camping with a group of say, four people, and each of you visit the creek to fill up water four times on your overnight stay.

With the return trip, that route will be padded down 32 times in just one overnight stay!

So, it’s worth consciously thinking about how you can disperse that traffic, perhaps by having a discussion with your hiking party and coming up with a plan.

This applies to anything that’s likely to happen multiple times while you’re camping in that spot. So, where you fill up water, go to the toilet, visit a nice viewing spot, return to your tent, or your camp kitchen (where you cook your food).

# 5 Do You Really Need a Crackling Campfire?

Alright, this one tends to get people a little bit fired up (#punny). Have you ever asked yourself if you actually need to have a campfire?!

I mean, how dare I suggest going without a campfire!

Campfires are where memories are created, where romances are kindled and shooting stars imprinted into our nostalgic, sappy human memory banks—we can’t not have a campfire?!

But here’s the thing, if you’re hiking, it’s not the most environmentally-friendly way to enjoy your time in the wild.

Let’s just review the considerations you should be making when deciding whether having a fire is a good idea in your camping location.

Firstly, are you allowed to have a fire? Rules exist for a reason, so make sure you check online before you head out, so that you’re aware of any fire bans in place.

Friends together, minus the fire! Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

Secondly, is there an existing fire pit for you to use, or will you need to disturb the ground to make a new one? It goes without saying that burning is destructive by nature. If there’s not an existing fire pit, or the ground is particularly fragile, you may want to think twice about starting your fire.

Thirdly, is there enough firewood around the campfire that you can collect without leaving a negative impact on the environment?

Sourcing wood is a contentious issue. Even fallen, dead branches are likely to be a home to happy little creatures; bugs, small native mice, snakes.

Hiking wood in is out of the question unless you’re the hulk or something, and even then, carting wood across borders is super contentious. Many people are against it because it can spread disease and pests into new wilderness areas, dramatically affecting vegetation in the area.

And lastly, are you sure that you’ll have enough water to properly put the fire out once you’re done with it? If you’re not camped by a water source, I’m guessing you won’t.

Depending on the types of wood you’re burning, and how large the chunks are, a fire that’s been burning for a few hours will need a lot of water to put out. It’s not a matter of splashing 500ml on the hots coals and hoping for the best.

You’ll need to absolutely drench the fire through until it’s practically cold to touch.

So unless you have an unlimited supply of water, a fire isn’t a good idea.

Hearing all of that, to me, it just sounds way too hard!

Instead, why not just create a little moment in front of your gas cooking stove where you imagine you’re sitting in front of a campfire, passing around the Schnapps and humming kumbaya contentedly?

# 6 Approach Rubbish Disposal With Benevolence by Carrying Out All Rubbish, Not Just Your Own

It can be tempting to see rubbish out in the bush and think ‘what a pack of scumbags’ about the perpetrators, but just continue walking past without picking up the mess.

I fully get that there is some rubbish that will be way too gross to touch, especially if you still have a few days of hiking to go.

But I try to think about it like this; yeah the ones who left the rubbish are scumbags, but does that mean that the next people to pass through deserve to experience their filth as well?

Another way to look at it, especially with bits of rubbish like plastic bottles and small wrappers, is that perhaps it literally was an accident? Perhaps they tucked it safely into their pack side pocket and gradually, throughout the day, that Snickers wrapper made its crafty escape?

It certainly helps my soul to assume people aren’t scumbags, and you never know, it might help yours.

So, always pack an extra garbage bag, and pick up rubbish whenever it’s reasonable to do so. If you’re a real eco-warrior, packing a set of gloves will allow you to hike out gross rubbish too.

Photo credit: Jack Durr @hikingrat

# 7 Look After Your Personal Hygiene and the Environment by Using Low-Impact Methods

Now no one is saying that you have to totally neglect your personal hygiene while you’re out in the wilderness, but there are some adjustments to be made.

Firstly, when brushing your teeth, you’ve got to try the ‘eco-spray’. It’s this fun technique where after brushing your teeth, instead of spitting it out in one spot, you purse your lips and spray the toothpaste water out into the air like a spray gun.

Dispersing the water like this means that animals aren’t able to ingest large quantities (large for them) of the toothpaste water which will likely make them sick. It’s also more aesthetic for other travellers—if you do it right, no one will even notice you were there.

Check out the eco-spray technique here.

Secondly, it’s important to think about what washes and moisturisers, deodorants and sunscreens you’re using. Try to buy low-tox alternatives, and even better—have a think about if you really need any of it at all!

Make sure that you never use face or body washes in any water sources, and also try to remove sunscreen with a face washer before going for swims.

A common misconception is that biodegradable products aren’t harmful to natural environments. Let’s bust that myth right here.

‘Biodegradable’ means that it will eventually break down, but that process is likely to take at least 6 months. And, the process will be much slower when discarded in water, rather than on soil or sand.

So, it’s never ok to use any soap—biodegradable or not—in waterways while you’re out hiking.

Another common baddie that people tend to bring out into the wilderness is face and hand wipe cloths.

These are disposable, but not degradable—they can take 100 years to decompose!

No I hear you saying, ‘but I pack my face wipes out, like a good little eco-warrior I am!’.

And that is great, but it’s always possible to accidentally discard products, without knowing. And that’s why you always need to think about how to minimise the amount of non-biodegradable products that you bring into the wilderness.

If you really need to bring them, ensure that you source compostable brands and pack them out.

Instead of using face wipes, why not try using hand sanitiser for your hands, and a face washer and a bowl of water for your face and “everything else.”

And lastly, avoid strong scents when outside, like those in deodorants, moisturisers, perfumes and hair products. Using scents is inconsiderate to people, confusing for animals and also doing yourself a disservice. Make the most of being out in the wild, where it really doesn’t matter if you smell a bit—how liberating!

# 8 Share Your Travels Online Responsibly and Respectfully

Posting a ‘sick pic’ on Instagram of your adventures might seem harmless, but there are a few things to keep in mind when you do.

Firstly, how fragile is the vegetation in the location you’re posting about? Will increased foot traffic overwhelm and harm it? Are there creatures or organisms that require minimal disturbance to live and flourish?

Secondly, what skills and experience are needed to reach the spot? Will your #sickshot on Instagram encourage people to attempt their first abseil just so they can get their own shot? Will it require them to go off-trail, with navigation skills?

Thirdly, have you considered the history of the land that you’re walking on? For 60,000 years, Indigenous people walked, cultivated and cared for the land we live and adventure on today. When you’re researching your trip, think about these thing:

- Who are the Traditional Owners are?

- What has happened in the region in the past? Were there notable cultural meeting places? Did any colonial atrocities take place there?

- Are there any sacred places to avoid? Things like waterholes, mountains and rock structures.

And lastly—and this one might trigger existential self-analysis—how much influence do you actually have? And by that I don’t mean ‘how many followers do you have’, I mean how much do people listen to your opinions, follow your activities and look to you for a source of inspiration?

In my opinion, the answer for most people is ‘more influential than you think.’

So, when posting, there are few things that it’s really important to keep in mind…

Firstly, consider whether you need to geotag the exact location. Sometimes just tagging the national park, or the general locality is enough, encouraging people to use their own research skills and yearning for adventure to learn more about the area.

Secondly, use your platform as an opportunity to educate your friends, family and followers about the Leave No Trace principles. You don’t have to turn preachy, and you don’t even have to use the words ‘Leave No Trace’. Simply explaining the concepts is enough.

And thirdly, have you acknowledged the Traditional Owners of the land? Have you double checked with local Land Councils that it’s ok to post about that particular location, if you’re unsure?

Keeping all of these things in mind should help you to assess whether or not you should be posting your adventures, as well as the types of information to include or leave out.

Ellie Keft is a content strategist and an adventurer with a particular passion for multi-day hikes in Australia and New Zealand. Ellie runs content agency Hiatus Studios, where she helps regional Aussie business owners with their marketing, and produces tourism and adventure-based content for a range of companies and organisations in the adventure space. To check out her adventures, head to her Instagram account, @ellielouhere